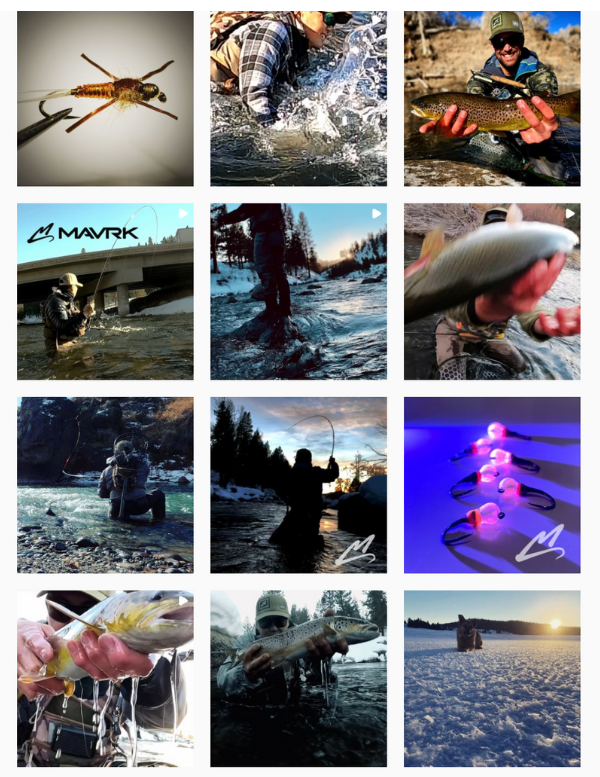

FLY-FISHING ON THE WEST FORK OF THE CARSON RIVER IN HOPE VALLEY, PHOTO BY BRIAN WALKER

STEWARDS OF TROUT HABITAT

As much as innovating gear and adopting overseas techniques may represent the future of the sport in the Tahoe area, anglers need waters—and fish in them—to sustain the activity.

Trevor Fagerskog, a Roseville resident who moved from Truckee in late 2020, is current president of the nonprofit sporting group Tahoe Truckee Fly Fishers and state chair of the California council of the nonprofit conservation group Trout Unlimited.

The latter group’s Truckee chapter focuses on habitat restoration in the Truckee River watershed. Fagerskog reasons that it’s not likely anyone is going to reverse the effects of climate change anytime soon, so they’re working to find natural areas that were modified by humans, then re-creating conditions that make the water more conducive to fish, even in a drought-threatened future.

Take, for example, the places where locals built ice dams in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

“Prior to refrigeration, they would freeze the river by damming it up, and then harvest the ice [in winter] and ship it on rail cars to San Francisco and points east,” Fagerskog explains. “When they dammed these rivers up, it just reduced all the gradient. They pulled all the big rock out of it, and it just creates these kind of barren, featureless areas—long stretches of 1,000 feet or more.”

While flat, empty pools may be ideal for making ice on the Truckee River, they’re terrible for fish that want deeper crevices where they can hide from predators and the water doesn’t heat up as much when flows are low in the summer.

Trout Unlimited identified several such spots on the Truckee River and has thus far restored two of them, one at Horner’s Corner near Hirschdale in 2017 and one upstream of the wastewater treatment plant off of Glenshire Drive—a spot they affectionately dubbed the “Toilet Bowl”—in late 2020. By installing rock weirs and creating depth, they give trout something more than 6 inches of tepid current to swim in at the peak of the hot season.

As for the Tahoe area as a whole, Fagerskog says fly-fishing is as good now as it’s been in a while.

“I think 10 years ago, it was in kind of rough shape—and the droughts haven’t helped,” he says. “But I think the conservation measures and people being more aware of catch-and-release practices and things like that have helped the fisheries around there.”

It shouldn’t be a surprise that fly-fishing anglers are especially attuned to the conditions of the habitats they frequent. Many study the water, land and air like holy documents, mentally cataloging an encyclopedia’s worth of hyper-local knowledge to give them an edge when they fish. They memorize the life cycles of dozens of types of insects to be sure they know what’s hatching and when and where, judge how river depth impacts water temperature and thereby oxygen levels, and experiment to determine the best flies and techniques for landing fish. Donahue calls it “cracking the code.”

While the sport tends to draw solitude-seekers, they are all connected by the waters they share.

Despite a strict catch limit, depending on the stretch of river, locals generally agree to catch and release only. “I could never imagine taking a fish out of the Truckee River and eating it,” says Scott Keith, who handles marketing for Trout Creek Outfitters and has been working with Sasaki and the Stinger. Area anglers typically abide by the informal “Hoot Owl” closures, as well: “That’s where we all voluntarily stop fishing when the water temperature is 67 degrees, usually around noon in late July and August,” says Fagerskog.

Anderson and Fagerskog also both sit on the Truckee River Basin Water Group, which provides them with knowledge of water releases from dams along the river. An influx from a reservoir can help lower the river temperature, while lack of flow can create situations where fish become stranded in ever-shrinking pools. Being able to anticipate these situations can be critical to the survival of prized wild trout.

“If they cut the flows for whatever particular reason, then we can mobilize a group of people to go out and essentially get buckets of water, put fish in them and move them into an area where the water is deeper,” Fagerskog says.

The Trout Unlimited state chair feels like conservation efforts have lost ground with the recent relaxation of regulations. For example, anglers are now allowed to use previously forbidden barbed hooks—which are more damaging and difficult to remove than barbless hooks, making them deadlier to the fish—and take two fish of any size from the confluence of Prosser Creek to the state line. Other waters in the state moved up to a five-trout limit and no gear restrictions.

The nonprofit uses social media campaigns and works with Forest Service rangers, biologists and wardens to encourage stewardship that takes the future of the river—and the fly-fishing that happens along it—into account.

“One of the things I tried to impress upon the Town of Truckee is that the Truckee River is the crown jewel of that area,” Fagerskog says, noting that with a shrinking shoulder season, influx of Bay Area transplants and other signs of pressure on the watershed, “They’re loving it to death.”

Adds Anderson: “A lot of us understand that this recreational resource, this aspect of the wild world that engages us so deeply, is fragile and facing an increasingly uncertain future due to climate change and growth-related impacts.”

A SPORT THAT’S HERE TO STAY

What is certain is that as long as there are places where trout gather under winged things that dip and dive, there will be people who want to both care for and catch them.

On a cool spring evening in May, one of those people, Donahue, is returning to civilization after a couple of hours on

the river.

“It was no luck today,” he says over the cricket chorus singing him home. As he walks, wary of his dwindling cellphone battery, he ponders the future of the sport, both in terms of the natural world into which it fits and the people who pursue it.

“I don’t do as much conservation work as I feel like I should be doing because I’m the benefactor of this amazing resource, but it’s something I plan to do more of,” he says. “And I do give a little money to a group that helps out both land and water conservation.”

Does Donahue think interest will continue to grow past the pandemic, once widespread vaccines make indoor activities a viable option again? Yes, he says, especially since it’s such a heavily male-skewed sport. He’s seen women increasingly taking up other sports and hobbies he enjoys—mountain biking and such—so he reasons that fly-fishing shouldn’t be any different. He’s noticed more young people expressing interest, too.

“It’s amazingly beautiful and peaceful to be standing in a river,” he says, “and that’s kind of where it starts. … You try it a couple times, you get frustrated, and then you’ve got to figure it out. And then you’re done. You’re hooked for life.”

Perhaps because of his “hooked” reference, Donahue wants to be sure he’s accurately representing the Truckee River anglers and their commitment to stewardship—to caring for the trout they fight to catch and then gently return to the current.

“You do realize we’re not killing the fish we catch?” he asks. “A lot of people might ask, ‘Well, why are you doing it, then?’

I don’t really have a good answer for that, except that I love these fish, and being amongst them is just really kind of magical.”

End Part 3

- Stewards of Trout Habitat

- A Sport That's Here to Stay

Leave a comment (all fields required)