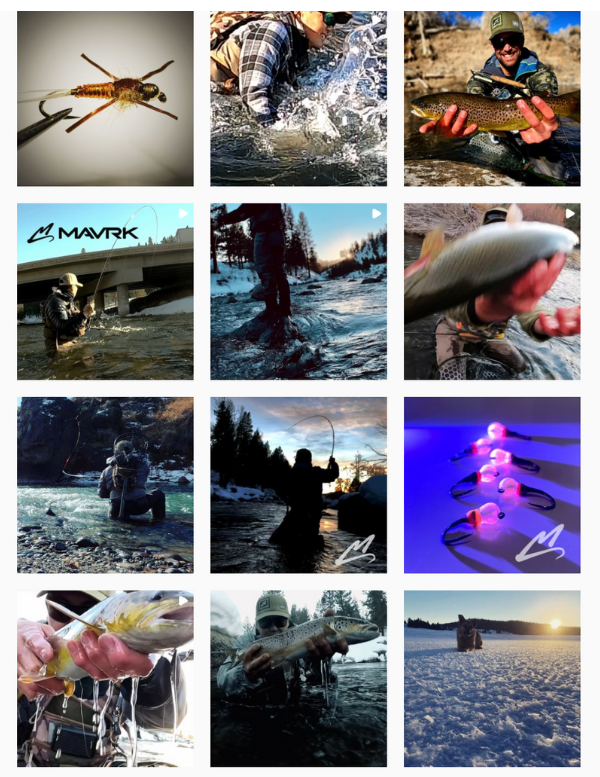

JEFF SASAKI AND HIS FOUR-LEGGED PAL, WINSTON THE AMAZING K9, BRAVE THE SNOW TO GET IN SOME CASTS ON THE TRUCKEE RIVER, PHOTO COURTESY MAVRK

EMBRACING INNOVATION

The Stinger represents something of a rebirth for Sasaki, who, after a career spent designing protective gear for cycling and other action sports, moved with his wife from San Diego to their second home in Truckee in 2016 (he also started and sold a company that manufactured iPhone cases from exotic materials). Once settled in, he didn’t want to do anything but “ride and fish” for a couple of years.

After 400 days of fishing, spread out over those two years, Sasaki realized that the only thing he truly wanted to do, work-wise, was improve every piece of fly-fishing gear he owned.

He started with the reel, aiming to create a device that improved his rod’s efficiency and allowed him to “fish longer and catch more” without adding to the shoulder and back strain common to the sport. Starting with a 3D-printed prototype, he took the design through 100 iterations, tweaking it so it would securely hold the line in place but also allow for the line’s fast and easy removal.

Instead of a reel winding the line into coils, the angler keeps the excess line either wound up on the Stinger or floating free, so the current can manage it. On the river, Sasaki demonstrates the Stinger in action, feeding line through his left hand in fluid motions that call to mind milking a cow or stripping corncobs of their silk. The slack forms a wobbly U that slowly unfurls in the water next to his thigh.

The main benefit to this design is the rig’s reduced weight. The Stinger Comp weighs 1.4 ounces, as opposed to a 5- to 7-ounce reel, which Sasaki says improves casting accuracy, reduces arm fatigue and makes the gear more portable.

The fatigue angle, which may sound negligible, is no joke. Sasaki’s preferred fly-fishing technique involves casting upstream, then holding the rod up and out over the water, keeping the tip just ahead of the fly traveling below the surface. It takes about 10 seconds at most for it to pass him to the point where he’s turned 180 degrees, prompting a fresh cast and another slow turn. Repeat. Then repeat again. Seconds add up into minutes, which stack into hours. Taking even 4 ounces off that rod can be a literal weight off a dedicated angler’s shoulders.

In June 2020, just two weeks before Trout Creek Outfitters opened its doors, Sasaki launched a Kickstarter effort that successfully crowdfunded more than $10,000. Stingers went out to backers in August of that year, and he’s since focused on developing the brand, messaging and marketing for his business, MAVRK.

GREG DERING WITH A COLORFUL RAINBOW TROUT CAUGHT USING TRUCKEE RESIDENT JEFF SASAKI’S INNOVATIVE NEW STINGER REEL, PHOTO COURTESY MAVRK

GREG DERING WITH A COLORFUL RAINBOW TROUT CAUGHT USING TRUCKEE RESIDENT JEFF SASAKI’S INNOVATIVE NEW STINGER REEL, PHOTO COURTESY MAVRKEURO INFLUENCE

The timing of Sasaki’s journey has also coincided with—and was shaped a bit by—the rise in popularity of a niche fly-fishing technique known as “Euro nymphing.” The technique is marked by lighter line, a weighted fly that sinks quickly instead of floating on the surface and colored demarcations on the line itself instead of a bobber—all of which pair nicely with the Stinger design. Sasaki admires Euro nymphing for its simplicity, saying it’s both welcoming to newcomers and satisfying for advanced anglers.

He explains that the U.S. men’s competitive fly-fishing team, seeking to nab an elusive win after years of trying at the World Fly Fishing Championships, began adopting the strategies of their more successful competitors some years back. Various proven methods developed for plucking fish from the waters of Poland, France, Spain and the Czech Republic converged into Euro nymphing, a short-range technique that focuses on the idea that most of a fish’s diet comes from sub-surface feeding. Even a cursory Google search for the term shows that guides, hobbyists and shop owners alike have been talking about Euro nymphing since 2017 and earlier, noting that it is effective for landing more fish in less time and dubbing it a trend as opposed to a fad.

Even so, Sasaki speculates that some longtime local anglers may be reluctant to adopt the style because of an adherence to tradition. Or it could be their allegiance to the idea of American superiority in all things, including a sport that was invented overseas, whether by salmon-seekers in Great Britain or Japanese fishermen enjoying tenkara some 400 years ago—or even ancient Macedonians, as some credit fly-fishing’s origins.

Babbitt of Tahoe Fly Fishing Outfitters says Euro nymphing is “the latest craze, no doubt.” But in his opinion, it’s not true fly-fishing.

“I’m a dry fly guy,” he says, referencing the storied tradition of angling with flies that kiss the river from above and stay at the surface—not sink to resemble nymphs recently washed from a rock. “That’s just who I am.”

There’s nothing better, he explains, than watching a fly drift down the river, then seeing a fish rise up to take it.

“But I’m a snob,” Babbitt says with a laugh.

Anderson is a bit more charitable in his assessment of traditional fly-fishing anglers’ willingness to embrace new technology and techniques. While he notes that the basic combination of rod, reel and line used to cast a weightless fly has been established since the seventeenth century, innovations to reduce weight, increase strength and enhance performance have improved the experience—without rendering “grandfather’s old bamboo and fiberglass rods” irrelevant.

“What I find more interesting is not the evolution in equipment, but changing attitudes in how to use it,” says Anderson. “For a long time, fly-fishers were generalists. We would buy a rod that would work for most types of trout water, typically a 9-foot-long 5-weight, and with it fish dry flies, wet flies, nymphs and streamers.

“Now, fly-fishing for trout is splitting noticeably into disciplines that focus on particular types of rods or gear setups or fishing techniques: two-handed Spey rods and their specialized casts, for example, as well as reel-less tenkara methods, which emphasize simplicity, and Euro nymphing gear and tactics that rely on longer-than-usual rods, fast-sinking flies and extremely thin lines.”

End Part 2

- Embracing Innovation

- Euro-Influence

Part 3 Coming Soon

- Stewards of Trout Habitat

- A Sport That's Here to Stay

Leave a comment (all fields required)